Lucas Trihey is an expeditioner, outdoor education lecturer, safety director for trail events and ESS principal. He’s trained for Swift Water Rescue and here explains the guidelines for when deep or fast-flowing water gets too dangerous. He also outlines what, if anything, event organisers can do and when it’s simply time to cancel.

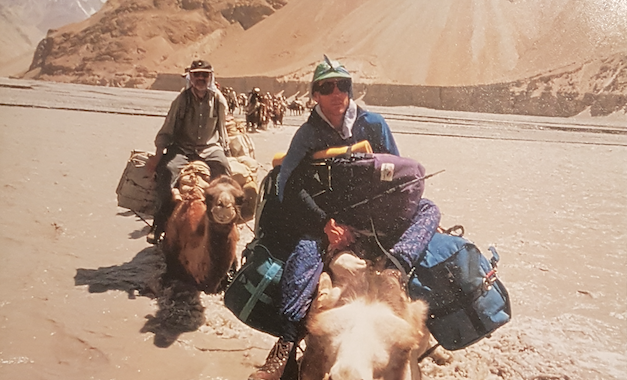

Photo: the author high and dry in big water on the north side of the Karakoram in Xinjiang, China on an expedition to 7400m Mt Chongtar in the 90s. Photo: Colin Monteath

Experienced trail runners know that “runner’s brain” can lead them to make mistakes and bad decisions when fatigued. Tired runners place their trust in organisers to make high-level decisions about matters like water levels, lightning or wind storms and bushfires. When organisers fail in this role people get hurt.

A good rule of thumb for Australian conditions is that organisers will need to implement extra safety measures to keep runners safe if:

The water is above knee deep, even if slow-flowing.

OR

The water is flowing faster than walking pace (5km/hour) even if shallow.

WHILE EVERY SITUATION IS DIFFERENT, SAFETY MEASURES CAN INCLUDE:

- Monitor the weather and creek, estuary or crossing levels in the lead up to the event. On event day organisers need to know if the water level is likely to rise, drop or stay the same. Watch out for tidal estuaries.

- Get experienced water safety people at the crossings – the common standard is Swift Water Rescue but there are other white-water paddling qualifications that may be relevant. These people won’t necessarily enable organisers to send runners across fast or deep water – but they will make better and more informed decisions to help the organisers.

- Position marshals on either side to show runners where to enter and leave the water. These marshals can also monitor the water level and let organisers know if the level rises or if the flow gets faster.

- Change the route away from hazardous water, this might be the day for that 2km diversion to the footbridge.

- Avoid crossings with waterfalls, rocks or rapids downstream.

- Avoid crossings with log, snags or overhanging trees downstream. With good reason these hazards strike fear into the hearts of white-water paddlers. Even slow-moving water has enough power to pin a person under water.

- A rope “hand-rail” can sometimes be strung tightly across a crossing. Only ever do so on the upstream side. This technique does not make it safe to cross deep or fast water but it can help runners stay upright in slow flowing or shallow water. Get an experienced white-water person to rig such a rope.

- Have a safety boat downstream of, or in the middle of a crossing. This doesn’t make a deep or fast crossing safe but can be good to look after nervous runners in slow or knee-deep water or if the bottom is rough.

- Unless it’s a known sandy bottom tell runners to leave their shoes on. Shoes help them stay upright and protect the feet.

- Trekking poles can help unsteady runners in water crossings.

- Runners can buddy-up to cross shallow or slow-moving water. Four, six or eight legs are more stable than two.

- Cancel the event or the leg that crosses water

- Event organisers who need to contend with water crossings need advice from experienced water safety people in the planning stages. Make plans to monitor levels and water hazards and have good water people lined up to help you make good decisions on the day.

WHAT NOT TO DO IN DEEP OR FAST WATER

- Rope use in moving water can be very dangerous in the hands of inexperienced water safety people.

- Never tie anyone in to a rope in moving water.

- Unless you have experienced water safety people at a crossing leave the rope at home, it’s probably time to cancel that section.

- Inexperienced safety marshals or event crew should not be placed at water crossings with deep or fast flowing water. There’s a lot that can go wrong and they just won’t know “what they don’t know”.